BROOK ANDREW: THE RIGHT TO OFFEND IS SACRED — Exhibition Review

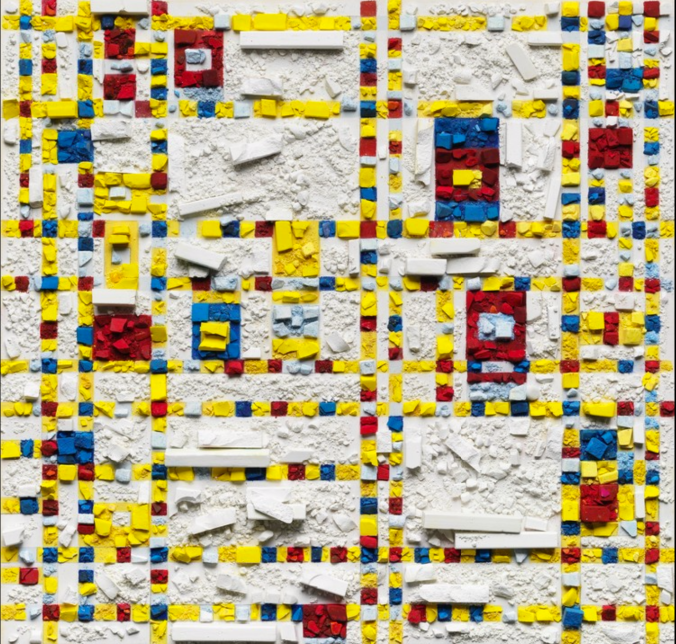

Hidden upstairs in the Ian Potter Centre, at the back of the Federation Square is a beautiful yet solemn experiential reminder of the mistreatment of indigenous cultures that has happened since the beginning of time. Brooke Andrew is an artist who explores controversial topics of race, gender, history and violence, and explores these ideas with curiosity and respect. ‘The Right To Offend Is Sacred’ is a comment on the discrimination and oppression of not only Australian Indigenous people, but Indigenous people from all over the world. He approached the topic in quite a loud and confronting manner, utilising a variety of media within the exhibition, bright colours and bold imagery. The juxtaposition of the traditional nineteenth century etchings and lithographs, and the radiant neon tubes of primary colours in the front section of the exhibition is intriguing. It allows the audience to understand the contemporary issue that still exists regarding the oppression of people with coloured skin, and it also highlights the obscene, powerful and sometimes overwhelming nature of these actions.

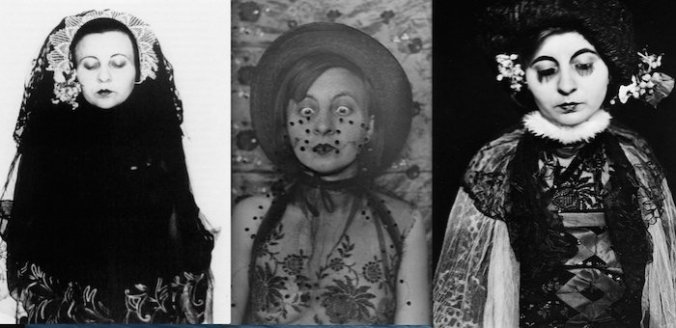

We can also look at how Andrew explores the idea of identity and spirituality within the exhibition, using many large photos of indigenous people in a large percentage of the works. The purpose being to make aware on these ideas of forgotten identities and subjugated religions and ideals, we are asked the question of ‘who are these people?’ and ‘what do they represent?’, as well as the question of whether the use of these photos is ethical and with permission from the subjects. The use of the black screen-print on a silver painted canvas gives the images their own unique quality which is Andrew’s appropriation in a sense. But it also begs the question of ‘cultural property’, both legally and ethically; these photos may have been taken over 70 years ago and so no longer hold copyright, however, does the use of this provoking photography defy traditional laws and customs of the people and cultures involved?[1]

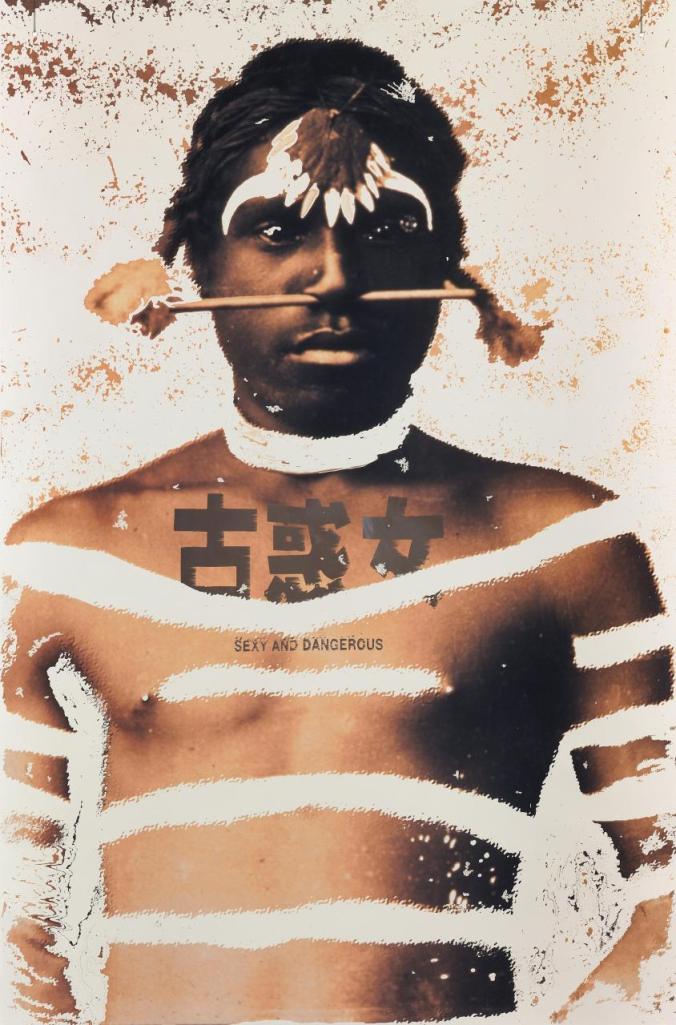

Brooke Andrew, Sexy and Dangerous, 1996.

One work in particular stood out to me as being a very strong, and clear abbreviation of the exhibition and Andrew’s approach to the oppression of indigenous people. “Sexy and Dangerous” 1996, is a large computer-generated colour transparency on transparent synthetic polymer resin. [2] The artwork depicts a shirtless, Australian Aboriginal male with a culturally significant wooden rod pierced through his nose. The image is then overlayed with white brush strokes and Chinese characters. Beneath the characters reads “Sexy and Dangerous”. My initial thoughts were that it is not dissimilar to a magazine cover; blown-up model shot with inciting and provoking text over the top. Andrew subtly, yet strongly communicates his discern for the glorification of indigenous people in this artwork, and commenting on the power relationship between western society and indigenous people, by exploiting our cultured minds that are used to seeing images like this on magazines and television commercials. Yet in this situation our mind does a double take; was that image used with permission from the subject, do those characters relate to the subject at all and what does ‘sexy and dangerous’ imply?

Overall this work is very provoking and powerful in its message, highlighting matters of oppression, appropriation, identity and image.

[1] Myers, Fred. “Ontologies of the Image and Economies of Exchange.” American Ethnologist 31.1 (2004): 5-20. Web.

[2] Andrew, Brooke. Sexy and Dangerous, 1996, computer-generated colour transparency on transparent synthetic polymer resin, 145.9 × 96.0 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

SHUJA HAIDER: THE SAFETY PIN AND THE SWASTIKA — Street Press Analysis (Zine)

In the early to mid 1970s the subculture known as ‘Punk’ emerged in several cities across the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia. The subculture was embodied by a broad range of visual and conceptual ideals, based primarily in punk-rock music, but branching out in to the realms of dance, visual art, literature, film and, most-notably fashion. The punk movement was about rebelling against modernism and ‘your parents’; most the punk movement’s population consisted of young people who wanted to set themselves apart from mainstream culture.[1]

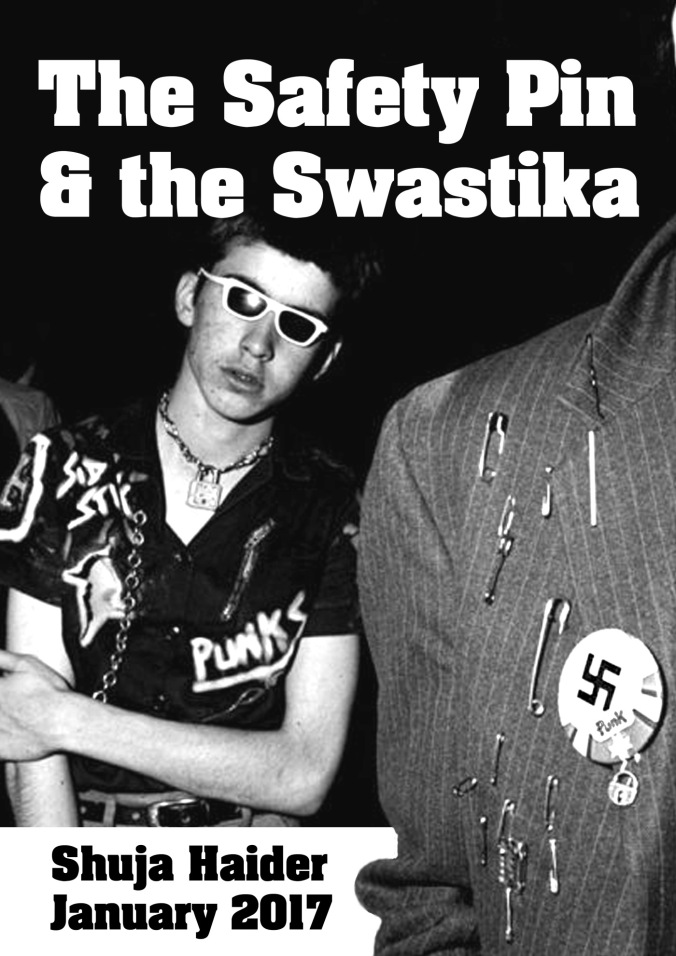

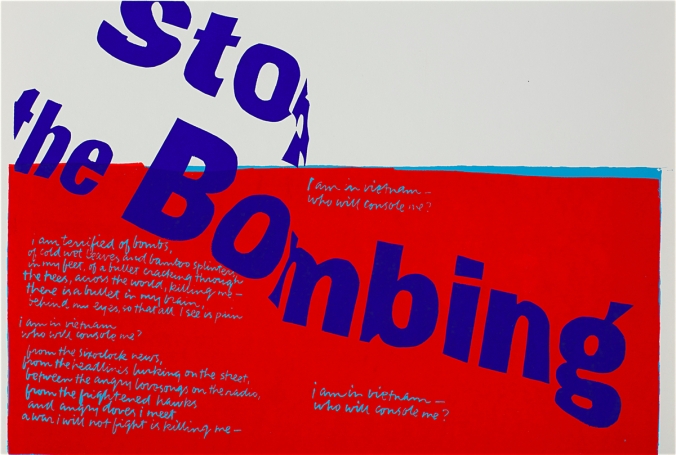

Shuja Haider, The Saftey Pin and The Swastika Zine Cover Image, 2017.

The aligned with a very cut and paste aesthetic — grungy and makeshift; this was inspired by the music genre they listened to. This was then translated into fashion through the tearing of clothing items, studs, badges and safety pins. It was here that the safety pin became a symbol for the punk subculture, and was associated with punks “even more so than with seamstresses.”[2]

And as for the swastika, the punks thrived on being ‘hated’, and so embraced the swastika as a symbol to represent them. The use of this icon was controversial as it was used by Hitler as an identifying symbol with during the Second World War, and thus, the general British population knew the swastika as something that signified the ‘enemy’.

Forty years on the safety pin and the swastika are appearing in modern society, but for entirely different reasons. We can now see the safety pin used as a symbol in a much more literal sense. It began with an American expatriate living in London, who wanted to inform people that she was safe to be around after the violence of the Brexit riots; she didn’t want to fall into the category of ‘alien’ to the British population, like so many expatriates did during this time. And so, she adopted the safety pin as a sign to show people that “they were safe in her presence”.[3] This idea was spread on twitter and ‘#safetypin’ was trending for a while. This trend eventually grew even broader and was picked up by magazines and newspapers, creating fashion trends such as diamond encrusted safety pins and over $1000 safety pin earrings. From a simple idea, the safety pin symbol is appropriated to fit within a different ideology and context; shifting its meaning from something rebellious and harsh, to something friendly and positive.[4]

It is interesting that in relation to design, something so simple and practical has become a symbol for such a broad variety of different parties and ideologies. The simple twist a metal wire has situated itself on the clothing of punks, popstars, expats and seamstresses over less than 100 years.

[1] Gill, Alison. “Deconstruction Fashion: The Making of Unfinished, Decomposing and Re-assembled Clothes.” Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress 2.1 (1998): 25-49. Print.

[2] Haider, Shuja. “The Safety Pin and The Swastika,” Subversion Press, January 2017, 1-12. Accessed April 3rd 2017: https://subversionpress.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/safety-pin.pdf

[3] Ibid.

[4] Myers, Fred. “Ontologies of the Image and Economies of Exchange.” American Ethnologist 31.1 (2004): 5-20. Web.

Particularly in the western and developed world, the orange speech bubble with a heart, head or smaller bubble is all too familiar. It’s the sign of approval, the sign of someone liking your post and, thereby liking you, which is more than just a ‘want’ for people but rather a ‘need’.

Particularly in the western and developed world, the orange speech bubble with a heart, head or smaller bubble is all too familiar. It’s the sign of approval, the sign of someone liking your post and, thereby liking you, which is more than just a ‘want’ for people but rather a ‘need’. Purrukuparli, 2002 by Maryanne Mungatopi

Purrukuparli, 2002 by Maryanne Mungatopi