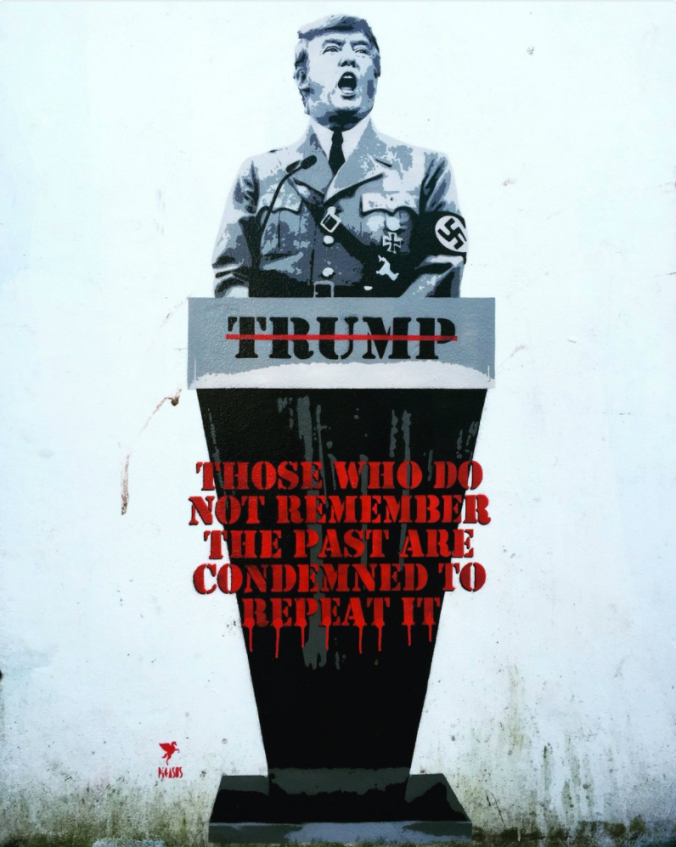

“The Kissing Coppers”, 2004, Banksy

It is 2017 and much like many of our peers, street art has gone through its own version of the old coming-of-age identity crisis; an eat pray love moment that may or may not have involved spending far too much money in Katmandu, for a glamping trip to a first world country. Street art has taken itself on a journey from its rebellious, self-expressive and disenfranchised beginnings and turned into someone who gets excited over buying a new vacuum cleaner and always insists on buying over-priced gift shop tea towels.

This change has come about quietly and slyly, but street art has lost part of its shock factor. The rebellious medium, that was once used to drive artists’ agendas has essentially transitioned the scene from the sub-cultural to the pop-cultural.

The values placed on street art have culturally shifted into a much more commercial platform. The most famous example of this is what society has chosen to do with Banksy’s art and it is interesting to see its fate aligns with many postmodernist theories. Banksy’s work became famous for his rebel personality and his witty critic of the government and political methods. However, with his new-found success, his work has now embraced a much more material culture, mostly on an aesthetic level of decoration.[1] There is no longer such a strong focus placed on the value of his product, but more what it gives when it is consumed. Banksy’ art has lost its true meaning by having it filtered down through various platforms of consumerism. For example, take his piece “Kissing Coppers”, spray-painted onto the side of the Prince Albert pub in Trafalgar Street near Brighton city centre in 2004, it became one of Banksy’s most famous street works. For years, it has been the two-fingered salute to the conventional art world, a poke in the eye for homophobes. But now, years after its creation, replicas of the piece can be found on a range of novelty pieces. Now only a trinket of consumerism. The fact that this once powerful imagery can be found on the likes of an overpriced tea-towel, has caused a power shift, demeaning the original imagery of its message.

It has become more commercially viable for street artists to move the art into a more commercial field, with Banksy’ success inspiring this change. The introduction of postmodernism’s ideas to street art, such as prioritising the consumption of images over their production has a lot to answer for. There is no longer such a strong focus placed on the value of a product but more what it gives when it is consumed; how much revenue it can bring in.[2]

The rise of pop culture and the blurring of the lines between low commercial culture and fine art explores the concept of taste from a new perspective. Postmodernism allows for, ‘different kinds of cultural manifestations to be valued equally'[3] and at the same time has stripped down many hard-hitting, revolutionary artists work, to be on the same platform as meaningless copies on trinkets, created as part of our conveyor-belt society.

[1] Sparke, Penny. (2004) An introduction to design and culture: 1900 to the present, 2nd Ed, London, ch.9 Postmodernism and Design, pp.189-197

[2] ibid.

[3] ibid.

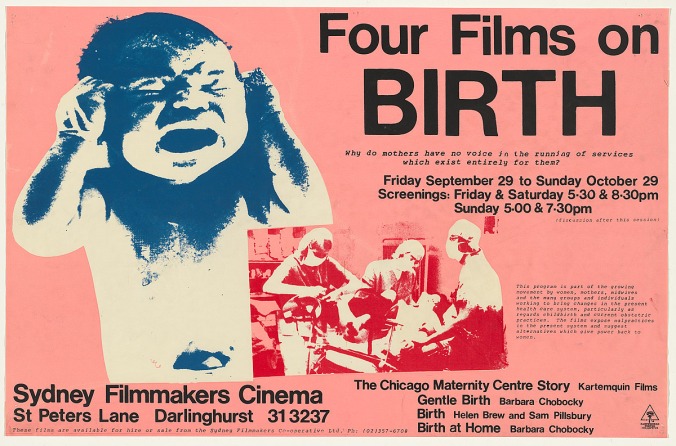

Sista Cortia was one boss ass bitch.

Sista Corita Kent was a Roman Catholic nun, who lived, studied and taught at the Immaculate Heart of Mary in Los Angeles. Kent’s work was encouraged by Vatican II (1962), a movement that aimed to modernise the Catholic Church and make it more relevant to contemporary society.

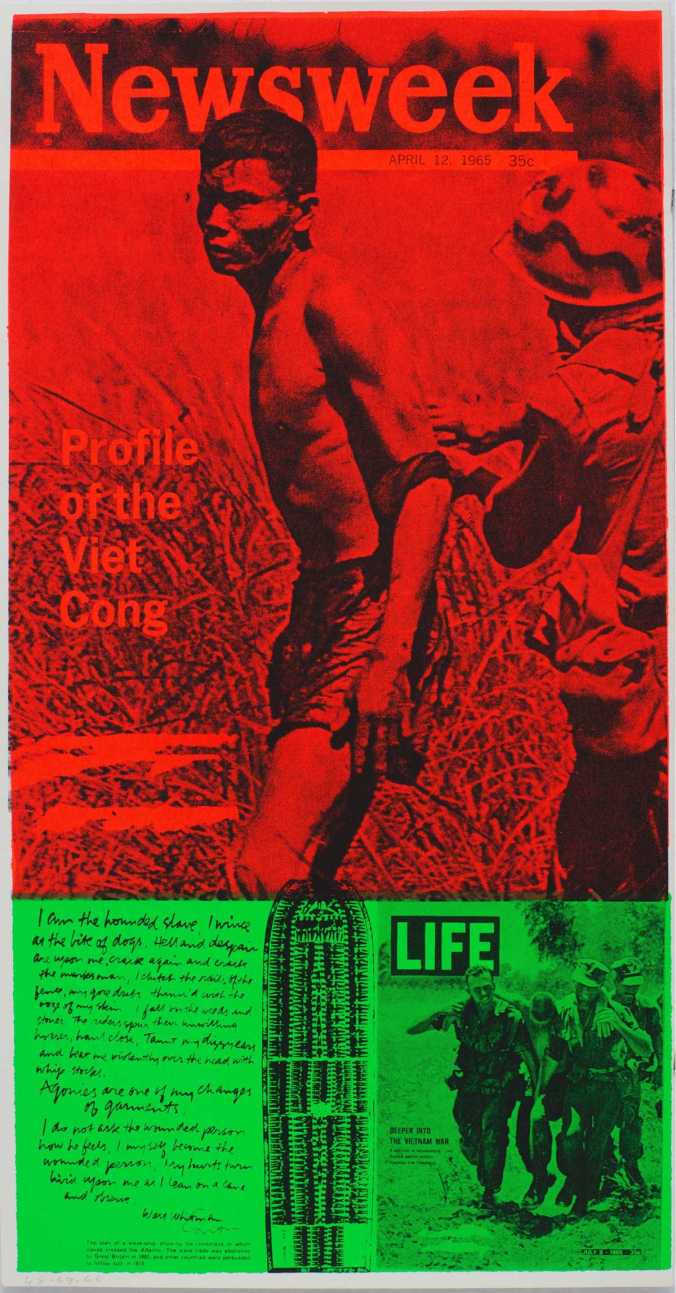

Her work draws on the high-keyed imagery of the pop art movement and focused on critiquing contemporary society. Kent aimed to draw attention to the world encompassing the everyday individual and created a platform that commented on social, cultural and political issues that arose from living in a mass media dominated society. Kent employed the same commercial styling and subject matter used in the Pop-art movement.[1] She borrowed signs and slogans, popular song lyrics and pieces of poetry; billboards, product packaging and magazine advertising, to develop her own distinct messages of joy, faith, love and protest.

Her keen interest in the emerging culture of a media dominated society injected a sense of frivolity into the art world. The simplified nature of her pieces meant Kent could bring design into the everyday household.[2] People could understand her final pieces, even if they didn’t know the thought process behind it.

This more contemporary way of production introduced using collaborative processes and enlisting the help of machines and technology to produce art. This use of collaboration opened endless possibilities and created the mindset that creativity was the key ingredient for good design and not just the processes used.

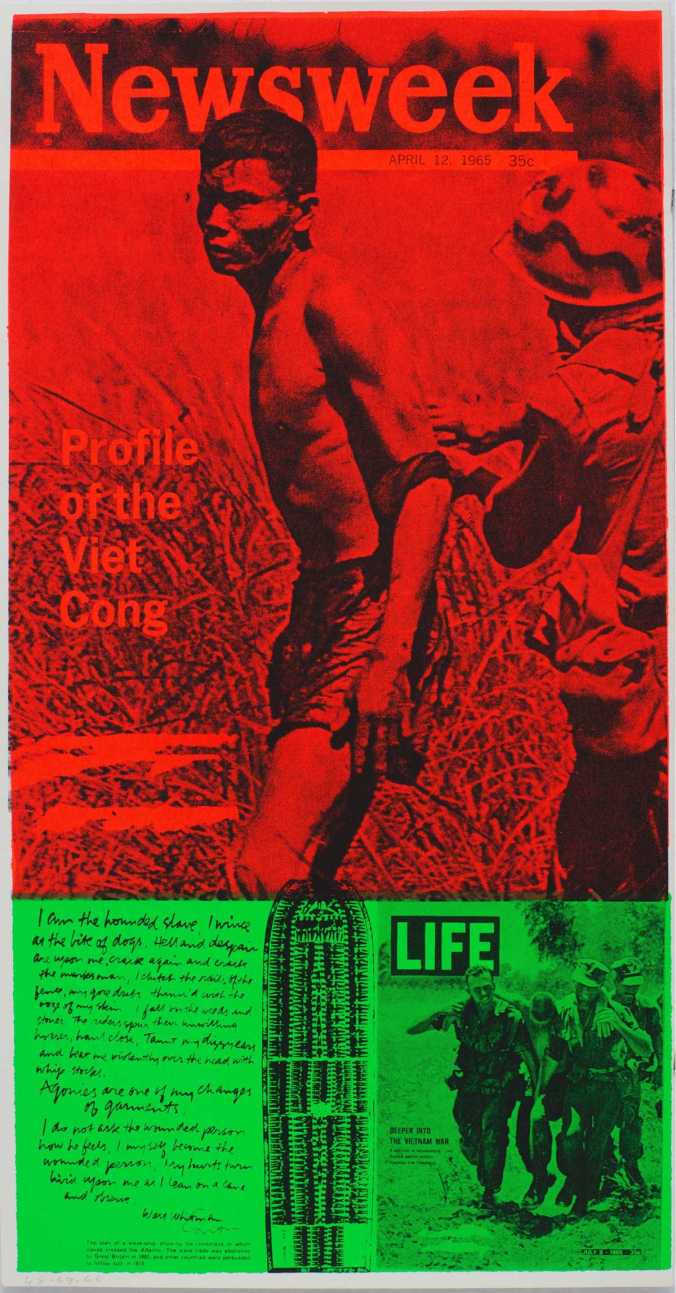

In her piece, “News of the week” the 1969 screen print, the equipment, materials and techniques she used heavily depended on the notion of mass-produced art; Pop Art. The piece forced society to view everyday visual culture as art. Kent’s’ style transcended the materials and techniques she made use of. Kent used the commercial technique of screen printing, to give her images an impersonal, reproduced feel. There was a depersonalization of style, the hand of the artist wasn’t so obvious, artworks looked like they could have been produced commercially rather than by an artist in a studio.

Kent made her art relatable and this was paramount in communicating a refreshing and new insight to the world of mass consumerism and political unrest.

Many of Kent’s ideas aligned with those raised in the reading “The Art of Revolution: Political Posters in the Red Planet Archive – No 75 Autumn 2005”. Olga Tsara raised the idea that artists believed the purpose of art can be to heighten the local community’s sense of identity and self-esteem. Art can be produced collectively to make political statements about how artists feel. Much like Kent’s art, where it was made for the community’s sake, not for her own. [3]

Kent successfully married pop culture with contemporary issues of faith and power in a critical period of unrest and in my mind, was a powerful voice.

[1] Osterwold, Tilman. Pop Art. [2nd] ed. Köln: Taschen, 1999. p.167.

[2] Thompson, Nato. Experimental Geography: Radical Approaches to Landscape, Cartography, and Urbanism. New York: Melville House ;, 2009.

[3] Tsara, Olga. “The Art Of Revolution Political Posters In The Redplanet Archive”. The LaTrobe Journal 75 (2005): 94. Print.